Since starting this series of interviews, I’ve wanted to highlight Rasha Diab, because she’s one of the most important people in my life. More than a co-author and friend, Rasha is truly an accountability partner: the first person I turn to process experiences, to understand emotions, to grow into new understandings, to repair harm I’ve done, and much more, including to laugh and cry and rage. Rasha has a way of holding potential—visualizing the best self—while staying grounded with what’s true now. This approach, I’m sure, relates to her commitments to and study of peacemaking.

This photo from the 2014 Watson Conference shows the two of us—Beth Godbee (left) and Rasha Diab (right)—standing side-by-side; wearing a mix of blue, black, and green; in front of a brick wall.

Specifically, Rasha’s work centers on the rhetorics of peacemaking. Her first book Shades of Ṣulḥ: The Rhetorics of Arab-Islamic Reconciliation (published by University of Pittsburgh Press and winner of the 2018 CCCC Outstanding Book Award) explores the possibilities of the rhetoric of ṣulḥ—a centuries-old Arab-Islamic peacemaking practice—as it is used to resolve intrapersonal, interpersonal, communal, national, and international conflicts. Her current book project focuses on the interconnectedness of Arab-Islamic traditions of conciliation, legal-political rhetoric, and rhetorical historiography. And other publications address violence/microaggressions, transnational ethics, pedagogy, and social and racial justice in writing studies, among other matters.

Rasha Diab, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor in the Department of Rhetoric and Writing and a faculty affiliate of the Departments of English and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. In this interview, she tells us about the courses she teaches, including peacemaking rhetoric, and how principles of peacemaking guide the work of everyday living for justice.

I hope you’ll check out this interview with Rasha, whom I know to strive for ethical consistency, for living out commitments, and for peace aligned with justice. Her work as a scholar informs her everyday life, and her scholarship provides guiding principles, some of which she shares here.

This photo (taken late at night, in a mostly dark room) shows the two of us—Beth Godbee (left) and Rasha Diab (right)—in the midst of work and talk. Rasha is drawing out ideas on paper, while Beth leans back in a chair. We’re surrounded by computers, mugs, and other objects: sitting around a messy kitchen table.

Interview with Rasha Diab, Ph.D.

1. Tell us about yourself and how you came to study and teach peacemaking.

There are many influences leading to my work today, including my family (and especially my father who was a lawyer), experiences in graduate studies, world events, and commitments that drive me. I’ve told a bit of my story in this podcast interview, and there are many more stories that are harder to tell—stories about epistemic violence that led me to peace studies, feminist studies, historiography, and cultural rhetoric, though I only came to this understanding with time.

As I piece together the realizations of why I do the work I do, which centers peacemaking, I realize there were many moments of witnessing violence and wanting instead to reach toward peace. For example, I came from Egypt to the United States in 2002, a little over a year after 9/11, and I remember a professor asking me that fall: “Do you know Osama bin Laden?” The Islamophobia, xenophobia, and racism were clear: packed into the many incredible assumptions in this question. And this question was just one of so many microaggressions that have stacked up over time.

Over time, the more I’ve read and studied, the more I asked: how can a person like me see themself in the scholarship? This question motivates me to seek sources sometimes far afield and to weave together many threads—from feminist studies to transnational rhetoric—in the pursuit of peace. The goal is truly countering violence, including epistemic injustice, or what Jacqueline Jones Royster refers to as “Western dominance in interpretive authority” in an article I love, “Disciplinary Landscaping, or Contemporary Challenges in the History of Rhetoric.”

2. What sort of courses do you teach, and how do you approach those courses?

I teach a range of undergraduate and graduate courses, including the history of rhetoric, cultural rhetorics, feminist rhetoric, transnational rhetoric, and peacemaking rhetoric.

Across these courses, we highlight assumptions about knowledge, relations, and communication. We ask questions like:

- What are communicative dynamics? Who is and is not communicating? Who is listening and being listened to—and when, where, how, and why?

- What communicative dynamics result in functional, healing relations and which in dysfunctional ones—and not only with ourselves and other people, but also with institutions, narratives, and even knowledge itself?

- How and why do we learn to use words to promote peace or hide violence (or to promote violence under the guise of peace) and, similarly, to highlight or obscure our roles and responsibilities?

I hope students ask these questions and others to continue lifelong learning.

3. Could you tell us more about peacemaking rhetoric? What do you hope students take away from that course?

We live in a world that’s so beleaguered with violence and justifications of violence that understanding and working toward peace is hard. But it’s easy as well. We need to understand that we can’t get at peace by just understanding violence. Instead, we need to become way more savvy—politically, culturally, and historically savvy.

Additionally, we need to find and study the abundant knowledge of peacemaking. Too often, superficial knowledge is instrumentalized and packaged to cater to the individualistic worldview in ways that will never feel satisfying and will never bring about healing. True healing takes place when we invest in rectifying harm (often historical and intergenerational) and proactively establishing peace and justice. Therefore, we need investment in understanding relational dynamics—the communicative dynamics I was getting at before. And one of these dynamics is power.

I hope students come away from the course asking about relations and power and stepping out of the games that get us trapped in power over. For example, if we focus on language like a “zero-sum game,” we basically recycle superiority logics. Or, if we turn to a “win-win solution,” without examining privilege and entitlement, we’re unlikely to counter injustice and instead entrench distrust.

We might think and profess that we’re doing conciliatory work, but such games or “solutions” inevitably create more harm. This sort of language distracts us from what might actually bring justice. The road to peacemaking is emergent and recursive and messy: not because the road to peace is difficult but because we often find ourselves too far in the other direction and too stubborn to even acknowledge that.

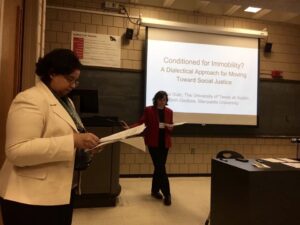

This photo from the 2016 Watson Conference shows the two of us—Rasha Diab (left) and Beth Godbee (right)—co-presenting: both with heads down, reading notes, standing at the front of a classroom.

4. Your first book, Shades of Ṣulḥ: The Rhetorics of Arab-Islamic Reconciliation, addresses a centuries-old Arab-Islamic peacemaking practice—ṣulḥ—and its potential for resolving intrapersonal, interpersonal, communal, national, and international conflicts. What do you want readers to know about this book?

As a starting point, I would like readers to know assumptions about “cultures of peace” and “cultures of violence.” There are so many myths about both peace and violence, and these myths hide peacemaking traditions and practices. The book intervenes into these myths, which I got to know well through questions I received over the years. Some were dismissive, some were hostile, and some were gifts because they offered a helpful nudge to be a better researcher, writer, and human being. Let me share some:

- If peace is a natural disposition, then how can we teach and learn it?

- What do you mean, there is a peacemaking tradition in Islam? How is there a peacemaking tradition in Islam if there’s only hudnah (truce agreements)?

- So, are you saying Islam is the answer?

- How can you talk about institutions or systems being violent? They aren’t sentient.

- How can you study peacemaking in Islam when Islam is such a violent religion?

- Why are you even studying this? Are you an apologist?

These questions are part of the backstory (one that helped me understand readers’ assumptions), but the backstory also includes me being moved through another set of questions:

- Are there available means of peacemaking? If yes, how are they known? If not, what political desires make us not know them or not invest enough to know them?

Knowing about these available means historically, not just rhetorically and politically, is crucial to countering chronic problems.

Peace is not just a happy state. Peace manifests within a cluster of other discourses (including memory/forgetting, political prudence, conceptions of harm) that allow or impede the process of thinking, working, and acting on peace. In short, peace cannot be understood without justice, history, or action. (This is why you and I keep centering the term “actionable commitment” in our research and lives.) Professed peace is different from realized peace. It’s not enough to limit violence. It’s important to strive to affirm rights, promote life and well-being, and establish and sustain systems that enable both.

Circling back to Shades of Ṣulḥ, I trace ṣulḥ cases across time, contexts, and types of interaction, and I do this because I want readers to see the flexibility, longevity, and applicability of ṣulḥ as a peacemaking tradition. Like all peacemaking practices, it can be used imperfectly or to justify injustice. True ṣulḥ, however, promotes justice and peace. The cases studied separately and together demonstrate its potential and continued relevance.

5. A lot of your work takes a historical bent. Why?

Violence and peace always have a context. Though each instance might seem unique, that’s typically not the case.

History—and by this I mean both remembered history and ignored or forgotten history—has a role to play in understanding the available means of violence and peace. And this is why I focus on diplomacy and the intersection between peace and pedagogy, for example. There’s much to learn about how peace practices (and violence practices too!) are woven deep into institutional memory and systems and people. Peace doesn’t just happen.

When I look at an encyclopedia from the 15th century and find that a whole essay (1 out of 10) is devoted to diplomatic peacemaking relations, I can see how the knowledge of peacemaking rhetoric is present. I can use this as a starting point to identify peacemaking before and after that historical moment, and this highlights continuity and versatility: these people have peace thinking. It’s not just a “one of a kind” document.

So, yes, my work has a historical bent, but that hopefully reminds us (again and again and again) that violence and peacemaking today are rooted in history.

6. How do you strive toward “everyday living for justice”?

My research, teaching, and learning are all “everyday” to me. I try to reflect and act on what this work continues to teach me, which includes a number of guiding principles. These include:

- the need to balance internal and external work: to make reflexive self-work a priority alongside work with others and within institutions. In other words: Peacemaking is not the job of other people.

- respect for my own and others’ boundaries, which includes acknowledging my own sovereignty and right to be the person I am and also acknowledging others’ sovereignty and rights. I’m not an extension of another person, and they are not an extension of me.

- understanding that the language of rights has always been entangled with the question of “what is right?”—a question to ask on a daily basis. What is right for me has nothing to do with the inalienable rights of another person.

- recognition of the multiple dimensions of personal and structural violence: direct, structural, and cultural dimensions of violence work together, so that a single act of violence is never just a single act. I resist facile stories that deny the power of context and the ever-present legacies of power.

- compassion for the long process of learning and unlearning, for peeling away layer upon layer of pain and hurt and individual and collective traumas. Compassion is needed and also not enough.

We all benefit from the pursuit of peace. We have a long way to go to unlearn violence, to learn peace, and to act on peace. The road will have many detours and setbacks. It is our commitment to the long haul that matters.

So, to do the work of peacemaking, we need a different relationship with time. The work will never start if we have a desire to hide violence from ourselves. Instead, we need to ask about what we’ve hidden. And why. And to grow the capacity to embrace our shadows.

When what we find is intolerable, then its counter (or intervention or critique for) guides us to doing things differently—in reaching toward justice and peace.

—

This interview is conducted by Beth Godbee, Ph.D. with Rasha Diab, Ph.D. for Heart-Head-Hands.com.

In addition to supporting the work of Heart-Head-Hands: Everyday Living for Justice by subscribing via Patreon, consider purchasing a copy of Rasha’s first book: Shades of Ṣulḥ: The Rhetorics of Arab-Islamic Reconciliation.

You can also read our co-authored article, “Making Commitments to Racial Justice Actionable,” which has led to ongoing research, including articles on understanding power and countering microaggressions and work-in-progress.

And consider subscribing to the newsletter and liking this blog on FB. Thanks!

Leave a Reply